Sexism Sells: The Misogynistic Depiction of Women in Advertising

By Medha Chandorkar, WIFP

July 2013

The second-class citizenry of women is nowhere as evident in the industrialized world as it is in the fashion advertising industry. The primary consumers of fashion are females, and yet, if one were to glance through a stack of fashion magazines, the primary audience would seem to be male.

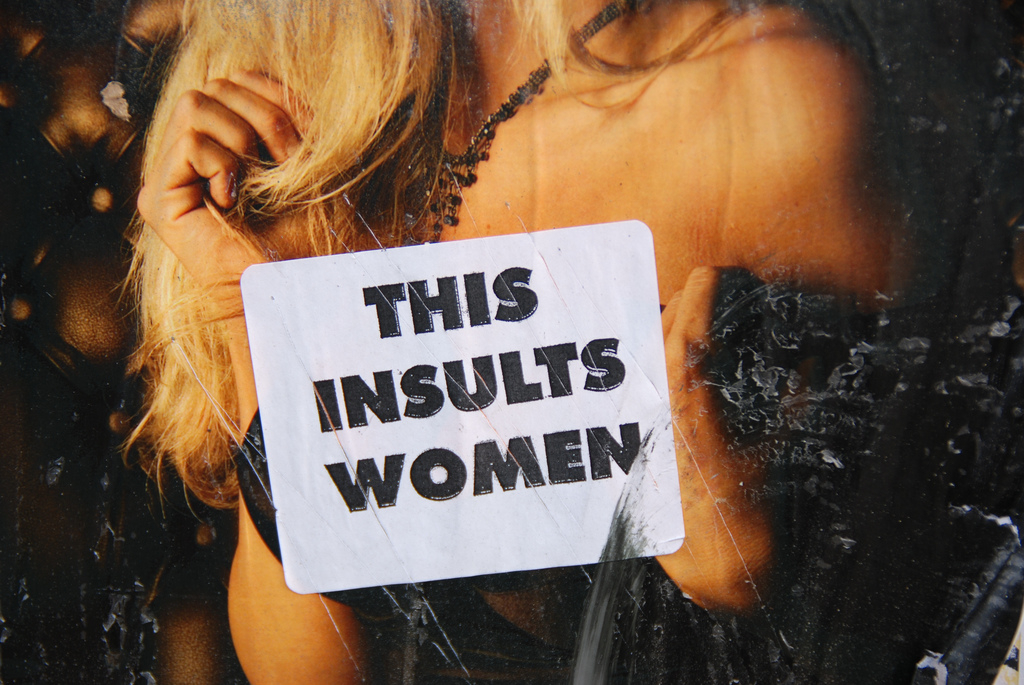

Women are invariably portrayed as sexualized objects, with bags over their heads and bruises on their bodies or in subservient, sexual positions to men, no matter what is being sold. The infamous 2007 Dolce & Gabbana ad (shown)that depicted a gang rape received great backlash, but such images have become even more popular today. To cite just a few recent examples, Johnny Farah depicted a woman being strangled by a belt, Red Tape menswear had scantily-clothed women in vending machines, and boutique store Blender hung sexualized parts of women’s bodies on hooks dangling from the ceiling. Women, the message seems to be, are literally just meat.

Objectifying women is obviously damaging to the struggle for gender equality, but what’s worse is that the pre-eminent creative minds behind these ads are not lowly designers who must follow the tide or risk losing profits. They standard of sexism is set by the elite of the fashion world: the Tom Fords and the Jimmy Choos. Their creative departments and ad designers have deep pockets and the influence to set the tone for the rest of the industry, yet they continuously revert to the same trope: women as victims, their bodies as sex.

Why? It’s simple. Only 3% of U.S. creative directors are female. When men are the only ones creating the ads, they will create it from their own viewpoint of what is attractive and desirable. Male sexual aggression and passive, objectified women become the norm, and when companies are confronted with the sexism inherent in their images, they deny it. In response to the backlash against their gang rape ad, Gabbana refused to apologize because he was just portraying “an erotic dream, a sexual game.” One might think that sometime during the lengthy creative process, someone would have mentioned that being held down by four men is much more a form of threatening, scary, and harmful sexual violence than an erotic game, but that would have required a woman’s perspective. And because women aren’t present in the boardroom or the design room or any sort of room in these companies, their voices are not heard and their perspective goes unnoticed or, worse, dismissed.

Furthermore, in the words of Jean Kilbourne, creator of the award-winning film series “Killing Us Softly,” advertising is not meant to sell us objects, but concepts. Companies want us to keep buying their products, so they portray women as inferior and flawed, while presenting their objects as the cure to become beautiful and perfect. Of course, the cure is temporary, until next season’s fashions, or impossible to achieve, with ever-skinnier models helped by PhotoShop. But when their goal is to create an endless demand, they must set an impossible standard and ensure that women forever feel “not good enough.”

These tactics, though sickening, are not just relegated to the world of fashion. They are prevalent throughout the entire advertising industry. Women’s bodies are used to sell everything from food (think beer commercials) to better mortgage rates. And because they’re so prevalent, it’s impossible to be unaffected by them.

The average American woman sees 400-600 advertisements every single day, and each one is a single subconscious reinforcement. One may think that they themselves are immune to this form of media, but the effect of quantity adds up quickly but silently. Studies have also shown that exposure to sexually explicit advertisements results in both men and women more strongly enforcing gender norms, accepting rape myths, and, specifically in the case of men, acting sexually aggressive towards women. Misogynistic advertising is yet another link in today’s rape culture.

Unfortunately, the problem is only getting worse. First, through globalization, the beauty ideals of the West are spreading around the world. A study comparing US and Indian magazines, for example, found that female models in India were beginning to copy Western poses and gendered stereotypes, with the added complication of racism through lighter skin. Second, the objectification is now also being applied to men. Kraft’s latest ads portray nearly-naked men with suggestive taglines (“The only thing better than dressing is undressing.”). This is not the gender equality in advertising media that feminists seek.

Advertising that demeans women is the norm in the industry today, and the problem is only compounded as we increase and expand our media consumption. Unfortunately, it’s also the kind of issue that seems too big to solve. How do we begin addressing a creative direction that spans almost all industries? In the past few decades, that question has been ignored for being too expansive, but the only thing that has changed is the number of misogynistic ads – and that number is only increasing.

We cannot hope to change rape culture if we do not change how we view women. We must begin with increasing the awareness that objectifying and humiliating women in the media is dangerous for everyone.

The Women’s Institute for Freedom of the Press

The Women’s Institute for Freedom of the Press